Jiankun Lyu, Sheng Wang, Trent E. Balius, Isha Singh, Anat Levit, Yurii S. Moroz, Matthew J. O’Meara, Tao Che, Enkhjargal Algaa, Kateryna Tolmachova, Andrey A. Tolmachev, Brian K. Shoichet, Bryan L. Roth & John J. Irwin (2019)

This paper has already been thoroughly highlighed several places, such as here and here, so I'll just summarise what the main take-home messages are for me.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Highlighted by Jan Jensen

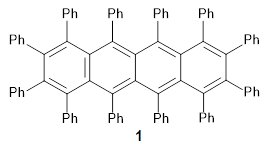

Figure 3a from the paper. (c) Nature

This paper has already been thoroughly highlighed several places, such as here and here, so I'll just summarise what the main take-home messages are for me.

- The size of the libraries (99 and 138 million) that are screened are truly impressive, especially when you realise that they sampled 280 conformations for each molecule! This required 1.2 calendar days on 1,500 cores.

- The libraries where made from 70,000 commercially available building blocks, which where combined using 130 known reactions. The molecules in the library should therefore be easy to synthesise

- Indeed, for one target they selected 589 molecules for synthesis and successfully made 549, for which they measured affinities.

- The selected molecules spanned the whole range of docking score, which results in a thorough test of the accuracy. As shown in the figure above, the scores can only really be used to weed out the very weak binders.

- As Derek Lowe notes "That definitely argues for setting up these virtual libraries according to expected ease of synthesis, because otherwise you could spend a lot of time making tough compounds that don’t do anything. People have."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.