Miguel A. Morales, John R. Gergely, Jeremy McMinis, Jeffrey M. McMahon, Jeongnim Kim, and David M. Ceperley Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2014, 10, 2355–2362

Contributed by David Bowler

Reposted from Atomistic Computer Simulations with permission

Reposted from Atomistic Computer Simulations with permission

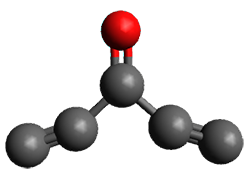

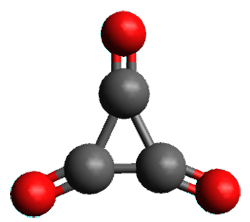

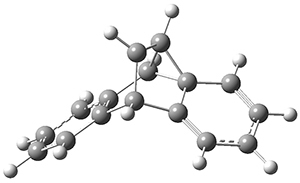

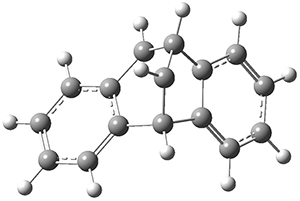

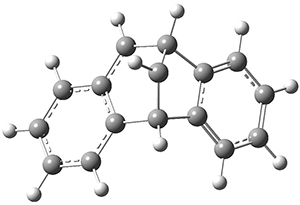

I want to start by noting that the modelling of water is enormously complex and controversial, and that I’m far from an expert; in water, hydrogen bonding, dispersion interactions and quantum nuclear effects are all important. The paper I want to discuss[1] performs detailed comparisons of the energies of different configurations of water molecules (drawn from a variety of dynamic simulations) calculated with several DFT functionals and quantum Monte Carlo (QMC). While there have been steps in the direction of doing MD with QMC, it is still too expensive to do this routinely; static QMC calculations have been shown to model ice extremely accurately[2,3].

The configurations that are tested are drawn from classical forcefields and path-integral MD (PIMD) with van der Waals corrected DFT (see here for a recent overview of approaches to vdW in DFT). The only test that is applied is the difference in total energy between the methods. This is, probably, the only test that could be applied, as force calculations in QMC are very expensive, but it raises an interesting question: is it the convergence of total energy always the best thing to test ? It’s certainly true in normal DFT calculations that forces and energy differences converge faster than absolute energies, and many calculations use this fact to reduce the computational overhead.

The classical forcefields used rigid water molecules (a standard approach to speed up the simulations) and for these configurations, the DFT errors are around 0.1 mHa (3 meV) per water molecule, with only small variations between functionals. This goes some way to explaining the success that can be found for some areas of water modelling with DFT (it’s important to note that dispersion effects are important and do reduce the errors).

When the configurations from PIMD are tested, however, these errors become much larger – around 0.3 mHa (10 meV) per water molecule for standard and vdW DFT methods. Only the hybrid methods maintain a low error (but they are still too expensive to use routinely with MD). Why does this happen ? Well, it appears that the major sources of error between DFT and QMC comes from the structure of the water molecule itself; when it is allowed to be flexible, configurations are generated that DFT describes poorly, but hybrids model better.

This failure can be explored further, using a correction scheme for modelling water in DFT[4] (where the error between DFT and QMC or coupled cluster calculations is decomposed in a many body expansion). They find that the major term contributing to the error is the one-body term, and show that the correction scheme gives excellent results. This confirms the difference between the errors for rigid and flexible water molecules.

The paper gives us an excellent insight into the limitations of DFT, and how it can be improved. It’s important to note that there are different ways of testing: PIMD simulations with vdW-DF2 have been shown to reproduce the experimental water structure almost perfectly[5]. It’s easy to get trapped into thinking that one particular approach or technique is best, or to become obsessed with methods: but experiment is always what must be tested, though it’s often far from trivial to work out how to compare to experiments.

[1] J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 2355 (2014) DOI:10.1021/ct500129p

[2] Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 185701 (2011) DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.185701

[3] J. Chem. Phys. 138, 221102 (2013) DOI:10.1063/1.4810882

[4] J. Chem. Phys. 139, 244504 (2013) DOI:10.1063/1.4852182

[5] arXiv:1402.2697 http://arxiv.org/abs/1402.2697